Immunity is a Spectrum.

2021-04-16 21:46:00 » blog, covid, ethics, medicine, philosophy

I should have wrote this a year ago. Some things are crystal clear in hindsight. Disclaimer: this whole piece is conjecture. I play with ideas. Increasingly I view my job as to get general forms and trends, and try out different ideas. Less black and white (ironic, coming from a moral absolutist). Which flows nicely into the hypothesis I’m putting forth, which seems pretty uncontroversial, but has horribly controversial rammifications if true: Immunity is on a spectrum.

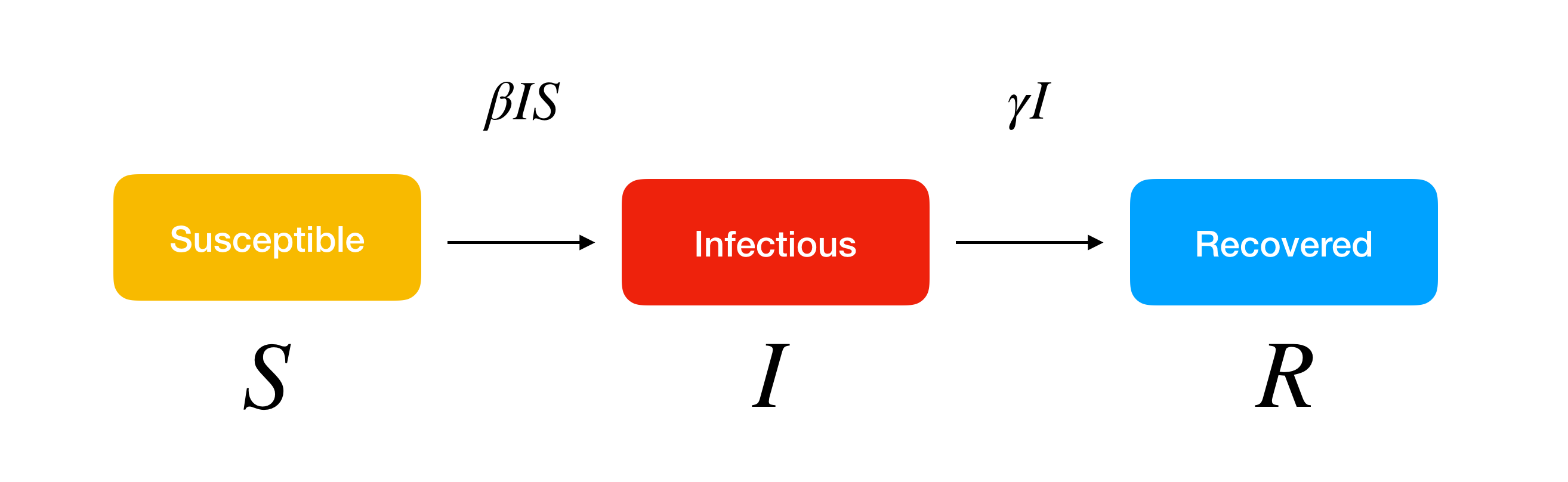

S-I-R Model

Early when COVID-mania started making its way through the globe, everyone jumped to these things called S-I-R models (susceptible, infected, recovered). The general idea being you can lump people into three general categories: susceptible, infected, and recovered. This is… well it’s a model, certainly. Models are useful insofar as they contain the underlying physics. The model of S-I-R is quite benign:

- The rate at which people transfer from susceptible to infected is proportional to the population that is susceptible, and infected, and a constant (let’s use β).

- The rate at which people transfer from infected to recovered is proportional to the population that is infected, and a (different) constant (let’s use γ).

What is this physics implying? There’s some magic constants β and γ that dictate how this disease will spread. There can be a lot of factors that go into β and γ. It’s hard to get a good guess unless you actually correlate against data… yadda yadda… the important thing is we’ve lumped everything into β and γ, and we’ve created ‘populations’. These populations do not consist of individuals, they are just populations. We assume that the constants apply evenly across the population.

If the S-I-R model is, in your mind, how disease spreads, you’re going to be thinking of things that influence the constants. That is to say, you think of how you can impact everyone.

The trouble, of course, is that these populations are quite vastly different in most cases. Not everyone’s β will be the same. A lot of people will acknowledge this- but here’s the interesting thing. Instead of asking “are there behaviors that individuals with low βs have in common”? They just write off that “your β is your β… and we just average the lot. We have to increase the average β by increasing everyone’s β”. This is foolish if there are some individuals whose β is practically zero, and some whose β is nearly one.

Severity is on a spectrum.

The other interesting aspect to consider is that even the difference between S, I, and R populations is not so black and white. It’s really more of a scale.

- Zero exposure to disease

- Disease caught, no symptoms, full recovery

- Disease caught, mild symptoms, full recovery

- Disease caught, ICU required, full recovery

- Disease caught, ICU required, partial recovery (chronic symptoms or sideaffects)

- Disease caught, ICU required, no recovery (death)

(Whether or not the last two are in the right order is an interesting question, but beyond our scope).

Being higher up on the list is better. Denying that there is a spectrum is nonsense. Being at level three is not a bad outcome- it’s a totally different cost than level 4 or 5. If your metrics do not capture severity, not only are you throwing away data that can be used to make appropriate cost-benefit analyses, you’re throwing away data that can help you understand ‘what are the risk factors for complications’.

Mild symptoms are better than requiring ICU admission.

Immunity is on a spectrum.

Immunity causes non-severity. The more immune you are, the more capable you are of fighting off an infection before things go south. We know that in the range from mild-symptoms to death, there are some pretty obvious risk factors. Would it be unreasonable to expand them all the way down to the zero-severity cases? I don’t see a clear reason why these risk factors should ‘cut off’ at the ‘no symptoms’ stage- immunity scales all the way across severity. Immunity is inversely proportional to severity.

Vis a vis, immunity is on a spectrum.

If it’s on a spectrum we can probably make mild shifts and nudges. There are things we can do to move towards the higher end of immunity beyond innoculation.

The presence of innoculations touting near β=0 levels of immunity seems to overshadow that the spectrum still exists… but it does nonetheless. If our goals are long-term health, we really should be seeking not to put all our eggs and resources in one basket by setting the β of one disease to zero, but seeking to holistically understand what causes a lack of immunity, and from there, foster generally high immunity across a wide swath of diseases. The answer may not be innoculation. The answer may be learning to master immunity and everything that goes into it.

Let me look both ways before crossing the street here… are you still there? OK. Let me walk right into this bus.

Fighting the next war.

COVID was mild. It was nothing. It has a fairly reasonable-to-understand set of risk factors (don’t be inflammed, don’t be obese, don’t be vitamin-deficient, don’t… well, you don’t really have control over your age). It should have been cake to bolster immunity, but it wasn’t. The general societal mindset has been “wait for a vaccine” or “it’ll just run its course”.

Will we learn from this folly?

Whenver I think about vaccination, I think about the general quote cited by those critical of militaries: “soldiers are always training to fight the last war”; “economists are always ready to fight the last depression”. Vaccination is reactive. General immunity is proactive.

Vaccine manufacturers are suggesting that booster shots will be required. Yeah… this is a rider on humanity. It isn’t “just the flu, bro”… it’s the new flu, bro. (Whether it was destined to be, is an interesting question). It will evolve, and continue to evolve. Immunity via innoculation has the same pitfalls of any corporate affair: information takes time to travel up from the field to planners.

What happens when we have the next COVID? Will we have to put a pause on humanity again? Or maybe, we can start looking back at this year, look at the data, and learn some valuable lessons about how immunity works and how we can produce general immunity for any disease. Is that too much to hope for?