Arithmetic Thinking is Smoothbrained.

2020-02-03 19:20:00 » linking, mathematics, philosophy

The development of early western philosophy is undoubtedly intertwined with mathematics, and in particular, geometry.

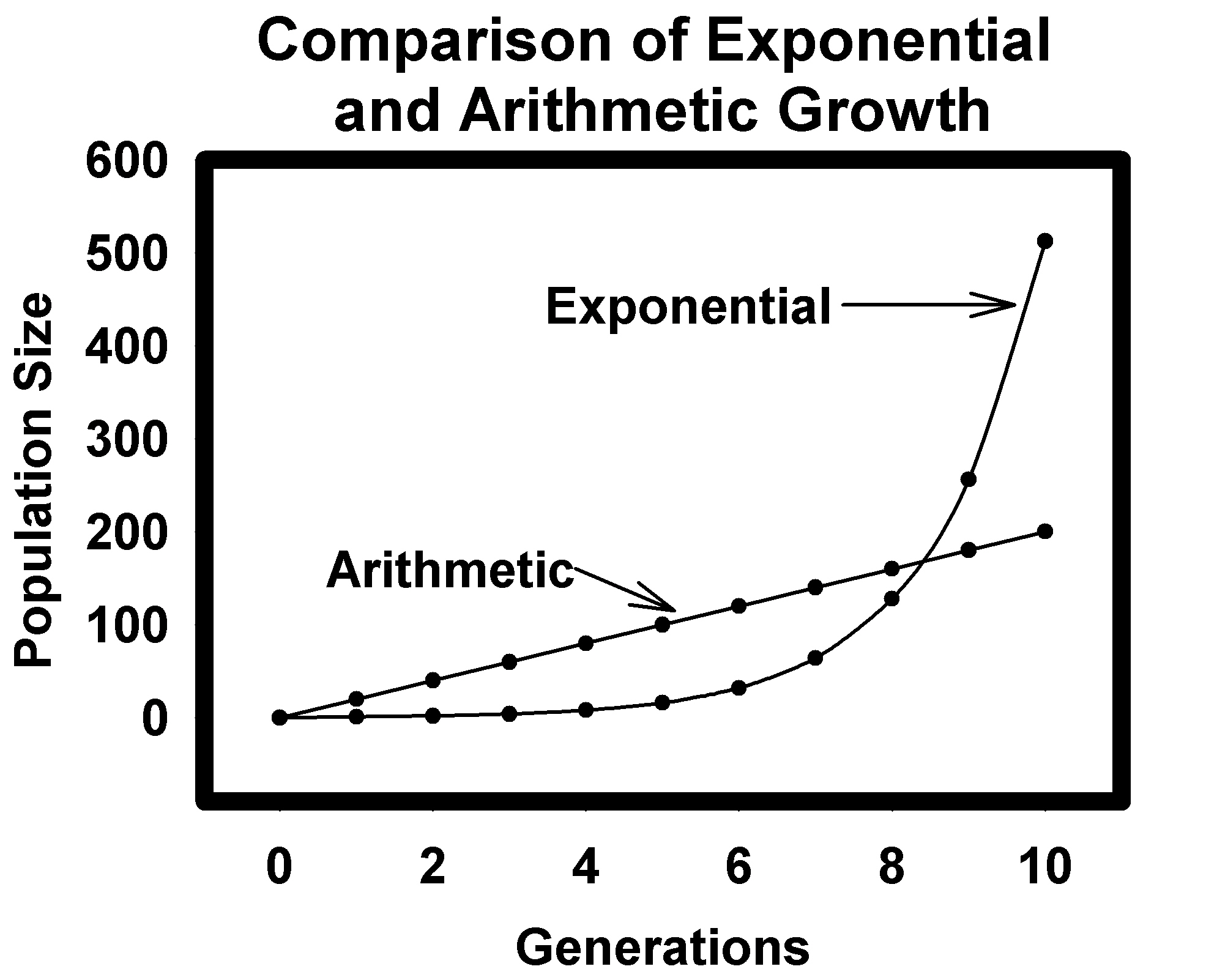

You may recall from your math classes, or from calculus two, geometric series and arithmetic series.

Approach

A geometric series is one where the next number is some constant multiple (a ratio, or proportion) of the previous, e.g.:

1, 3, 9, 27, 81, 243

An arithmetic series is one where the next number is some constant additive of the previous, e.g.:

2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14

While the typical mathematics course will help remind you of how these work by creating stories such as “One Grain of Rice”, the relation is actually inverse- the story emerges from the series, not the series from the story. The geometric series has many manifestations, all of which could be considered natural, from the Latin “nasci”, meaning to give birth. One begets two, the two beget four, the four beget eight; a flowering out by which the entire space may be filled even as the originals die off.

The arithmetic sequence, on the other hand, is a sterile one, a steady march by which gains are made begrudgingly and uninterestingly, if at all. There are no network effects. This does not describe a natural process.

Interestingly, this is further reflected by the etymology of these terms. Both terms have their origins in greek: ‘geometry’, or γεομετρια (γε ‘earth’, μετρια ‘measure’) regarding the surveying of land and nature; ‘arithmetic’ or αριθμητικη (art of counting).

The error of the arithmetic mindset is made even more apparent when we flip the progression in the other direction, however.

Geometric series: 1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16

Arithmetic series: 1, 0, -1, -2, -3...

As far as describing physical phenomena, the former makes much more sense than the latter: negative quantities do not exist, or at least, are unsustainable debts which must be repaid. The geometric series, however, can infinitely collapse and converge upon an essential truth.

Interactions

Let’s take this into two dimensions. A dimension is simply an orthogonal axis, an axis that varies independently of the first. Let’s consider the ratio 2 for some geometric series and arithmetic series.

Geometric: A = 2, 4, 8, 16, 32; B = 3, 6, 12, 24, 48

Arithmetic: A = 2, 4, 6, 8, 10; B = 3, 5, 7, 9, 11

We can visualize the effects that these two dimensions have on each other if we consider them as lengths of the legs of a right triangle. If you have some graph paper, feel free to plot it for yourself.

In the geometric series, the ratio progresses from 2:3 to 32:48 (which, if you notice, reduces to 2:3). The proportion, or shape remains the same. In the arithmetic series the ratio progresses from 2:3 to 10:11, or in decimal terms, from about 0.66 to 0.90909.

If we were to continue these series on, both do indeed continue growing unceasingly, but the ratios diverge. The geometric ratio always remains constant. However, with an arithmetic ratio, the ratio converges to unity.

Conclusion A: If all dimensions are geometric, the relationship between them does not change.

Conclusion B: If all dimensions are arithmetic, the relationship between them changes, and approaches, but never converges to, unity.

The keen eye would see that there are more possibilities, though.

Conclusion C: If one dimension is geometric, and the other arithmetic, the relationship between them diverges, in favor of the geometric.

From series analysis we know that this is true even if the ratio for the arithmetic is higher than the geometric. The arithmetic may have a short-run advance if its ratio is sufficiently high, but there is some point at which it dominates.

Where are we going with this? Early ‘western’ (modern ‘near east’) thinkers recognized the link between morality and beauty- and as such, were keen to the link that morality would have with proportion. It has been said that sin is an aspiration to that which is not possible- mirroring the approaching-but-not-converging nature of an arithmetic-arithmetic ratio.

Politics

The co-option of the term ‘progressive’ by some politicians and progressives is quite regrettable, as we can clearly see now there are many ways in which to ‘progress’. Save for the anti-natalists, verily, all people desire progression, at least in the form of begetting replacement offspring. The question is, by which algorithm?

Aristotle advocates for a geometric progress: “for if persons are unequal, they ought not have equal shares”; unequal shares for unequal merit. 10 times 3 is 30, a +20 increase. 100 times 3 is 300, a +200 increase.

The egalitarian, however, advocates for arithmetic progress: equal shares, regardless of merit. 10 plus 3 is 13, and 100 plus 3 is 103.

From this many practical ideas can be plainly illustrated (suppose, say, one modifies the sequence so one can influence their standing in the sequence- in a geometric progression, their efforts are multiplied and rewarded, whereas in an arithmetic progression, they are discarded and ignored). But the key really is a sense of proportion, and that there is good beyond the mere growth of a sequence. A geometric scheme allows for a sense of beauty and proportion that emerges not from the mere magnitude of numbers, but their relationship and harmony.

This may at blush sound like ‘slave morality’ as Nietzsche might describe it (accepting a lower position out of a trick the upper classes play), but it clearly is nonsensical as this same sort of thinking benefits the ‘masters’ as well.

The way out is not in a rat race of arithmetic progression, but in respect for divine proportion and the opportunities that multiplication offers.

Riffing on conclusion C, the arithmetic mindset is ultimately doomed if not alone.

The geometric mindset, being natural, cannot be extinguished- only ran foolishly against. “Whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them.” - Matthew 13:12

3 → 6 → 12 → 24 → 48

-1 → -2 → -4 → -16 → -32

The arithmetic sympathizers do have one option, though, and that is to eliminate all traces of geometric progression. It is only in the utter rejection of all proportion and ratio that the arithmetic approach can stand any chance. It may at times ‘embrace’ a geometric sense of beauty, but it will seek to add and ‘extend’ (extension is clearly a different process than multiplication), and ultimately ‘extinguish’.

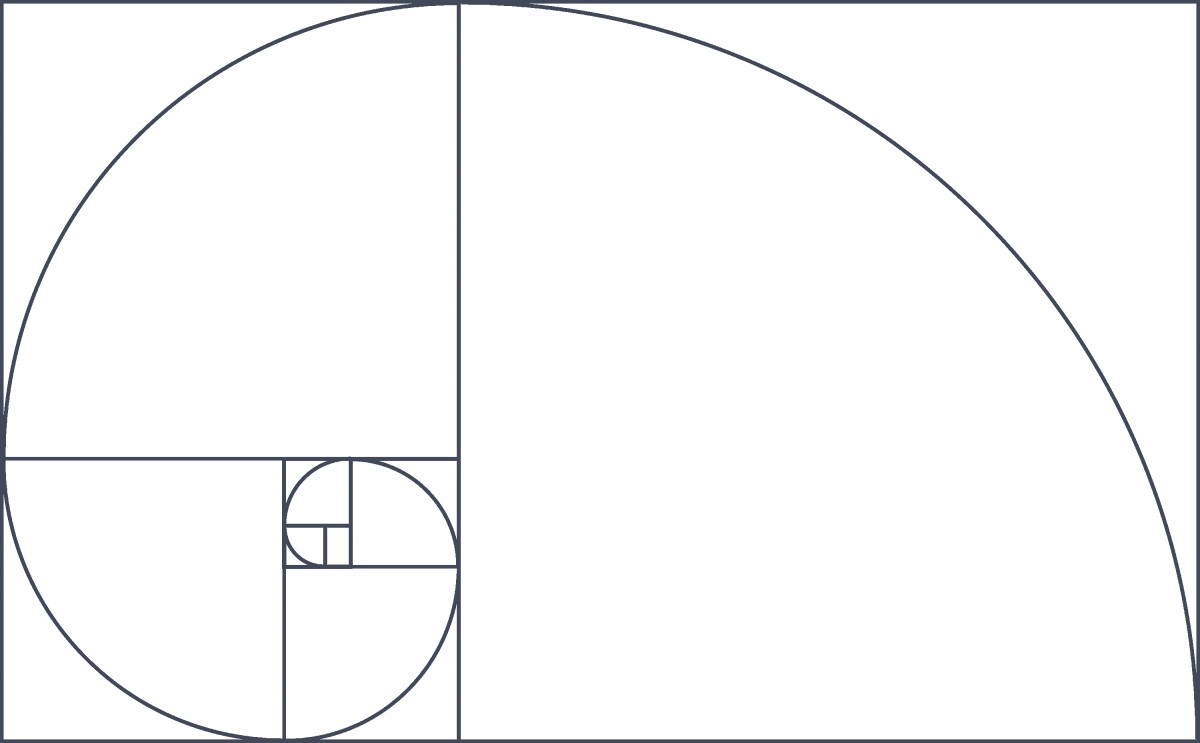

Golden Ratio

Arithmetic thinkers will often criticize the present distributions. They will rarely criticize the ratios, but instead focus on absolute discrepancies. The acknowledgement of ratio is itself a geometric idea. You may be well familiar with one such ‘golden ratio’, approximately 1.618, often by the symbol φ.

She’s beautiful, isn’t she?

The delight of this ratio is that squares of proportionately larger diameter can be arranged together to form a structure without gaps. It is not only geometric thinking that enables this, but also the correct proportion. The role of the geometric thinker cannot be merely to rebuke the arithmetic-minded, but to show them that a ratio which could accomplish just ends does exist. I do not argue that there is something about φ which is imbued in every circumstance- φ happens to work for packing boxes in this fashion (among other recursive patterns), but will not work for all problems.

The only ratio which the arithmetic-minded can comprehend is one-to-one, and even that, they must at some point recognize as unstable at best and impossible at worst. The rigidity of their ratio disallows any natural flourishing in nearly all cases. Nothing natural has a ratio of one. Even the ameoba can reproduce multiple times.

OK, fine. There is something neat about φ, or at least the concept it represents. It’s the magical ratio such that:

φ = a/b = (a+b)/a

It’s a ratio that allows for spiraling down (or up). It represents the idea that the same proportion exists amongst the small things as amongst the large things. That is to say, that you expect to see similar patterns on a macro- as a micro- scale.

Room for Imagination

You probably have heard of the Cult of Pythagoras. These swell fellows were of the belief that all numbers could be represented as integers, or fractions thereof. We today would call these rational numbers. It’s plain to see how would would imagine they could exist. Heresy, to these fellows, came in when geometry was introduced. We’re familiar with the pythagorean theorem,

a^2 + b^2 = c^2,

“The sum of the squares of a right triangle’s legs equals the sum of it’s hypotenuse.”

However, we know now that the solutions to y = x^2 are of the form x = sqrt(y), which are generally irrational numbers. They cannot be represented as fractions. Indeed, the poor arithmetic-minded cultists of pythagoras could not take the leap of faith required to accept an irrational solution even when the necessity stared them in the face. We see this today in new-atheist types, who having reduced the world so far down to an essential motive force that you could call God, refuse to call it God or at least treat it as such. Their a priori ‘rational’ framework doesn’t allow them the freedom for such concepts.

Geometric thinkers, even if they did not admit that the square root of 5 was a number, would nonetheless admit that the side length of a hypotenuse was real, existent, and useful to speak of. We see this a lot in the post-new-atheist types (e.g. Peterson), who recognize that you must call it God, even if not canonical and real in the same sense the rest of reality is.

The geometric mindset is a playful one which seeks the unknown and mystical.

Manifestations

Still not sure what I’m getting at? Here’s a cheat sheet.

Geometric:

- Flourishing (“flowering out”)

- The traditional family across multiple generations

- Reinvestment of labor and wealth

- Spread of ideas by network effects

- Learning from tradition

- “Big Bang” theory (or Creationism)

- Charity and free sowing of seed

Arithmetic:

- Sustinence

- Replacement populations

- Universal Income

- Extraction of surplus value; usury

- Ignorance of history

- Steady-state universe theory

- Stinginess and hoarding

… among many more examples. You have a brain. Think geometrically, and all will be clearer.

Can you think of other schemes than geometric and arithmetic? Sure! I invite you to think of them. I’d be interested to see your parallels.